Prince Rupert with dis dog Boye

The argument about which news sources are the most fact-filled or truthful is an old one. During the English Civil War, propaganda was used as a valuable tool to sway countrymen to support one side or the other—the Royalists or the Parliamentarians. Various newbooks on both sides were created to stir the pot and evoke fear in readers with the hope that they would understand that fighting the war was absolutely necessary. At the time, where you lived determined which side of news you were going to get. For example, if you lived in London, the midlands, and parts of east England where Parliament held the most influence and power, you would most likely read (if you knew how) and hear propaganda that supported Parliamentarian efforts and beliefs. If you lived in northern or western England or Wales, you were more likely to receive pro-royalist propaganda.

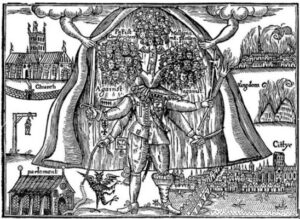

These newsbooks used several different types of tactics—not unlike what we see today—to persuade readers to take sides. For example, graphic images made from woodcuts might depict atrocities committed by one side against the other. Of course, the scenes were highly exaggerated and even satirical at times but nonetheless, they were effective in scaring enough people to align with the source.

Newsbooks also personally attacked either members of Parliament or royalty depending on the paper. Mercurius Britannicus favoured the Parliamentarians and Mercurius Aulicus and Mercurius Pragmaticus favoured the royalists. One of the more popular attacks made by Parliamentarians involved Prince Rupert. They claimed he would enter a town, rape the women, and pillage the homes, leaving chaos and destruction in his wake. They even accused his dog, Boye, of being bewitched and turning invisible so he could spy on enemy troops and report back to his master. Clearly, neither of these claims were true, but they were effective. It’s hard to imagine, but many people believed them.

‘The Puritans Nightmare’, (Parliamentarian propaganda, Circa 1643): On half of the figure ‘Papist’ and the other half a Cavalier, multiple weapons in hand. The kingdom burns in the background and the man hangs for not aligning with King Charles I and his Catholic wife.

They also attacked religion, specifically Catholicism. Since the 16th century when King Henry VIII began the English Reformation and pulled away from the Catholic church, England—with a brief intermission during Queen Mary’s reign—remained peacefully Protestant for the most part. The last thing the country wanted to do was once again enter into chaos and violence with a return to Catholicism. When King Charles I took the throne and married a Catholic Queen, many people believed he intended to revert back to the religion. Parliamentarians capitalized on this idea and spread rumours that the king planned to destroy the country in the process.

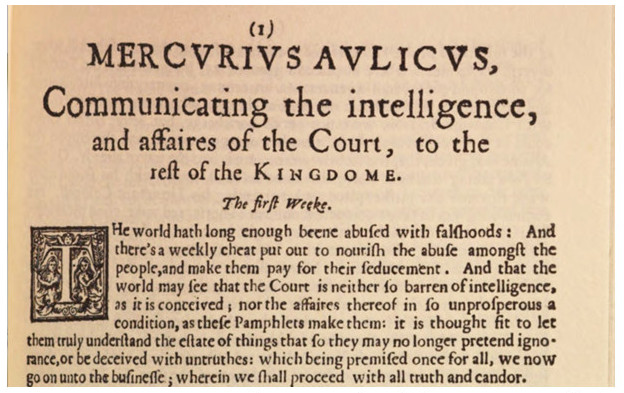

MERCURIUS AULICUS, a Royalist newsbook in support of King Charles I.

The first words in the inaugural edition of Mercurius Aulicus were, “The world hath long enough been abused with falsehoods,” a statement directly aimed at Parliamentarian propaganda “cheats” that purported the evils of the crown. The Royalists said “we shall proceed with all truth and candor”, claiming their opposition was lying to the public. Sound familiar? The goal was to provide another side of the story—the king’s side—and one he and his supporters hoped would convince readers to turn away from Parliament and take up arms for the royal cause.

In the end, no one really knew who to believe. In Shame the Devil, Colin gets his hands on a few newsbooks and becomes aware of the conflicting information written inside. Left with too many questions, Colin chooses to follow his heart and vows to take revenge on the Parliamentarians who not only killed his mother but stole his future as a free man.