Shame The Devil

PURCHASE NOW

England, 1643: The Civil War has created a great divide between those who support King Charles and those who would rather see his head on the block. Young Scot Colin Blackburne finds himself caught in the middle when he witnesses Parliamentarians murder his mother because of his father’s allegiance to the king. As further punishment, the family is sent to Yorkshire as indentured servants.

England, 1643: The Civil War has created a great divide between those who support King Charles and those who would rather see his head on the block. Young Scot Colin Blackburne finds himself caught in the middle when he witnesses Parliamentarians murder his mother because of his father’s allegiance to the king. As further punishment, the family is sent to Yorkshire as indentured servants.

Mistreated by his master and tormented by a Parliamentarian soldier, Colin vows to take up arms for the king and seek vengeance against the men who killed his mother. The only bright spot in his life is his unexpected, and forbidden, friendship with his master’s daughter, Emma Hardcastle.

With her father constantly away on campaign and her mother plagued by madness, Emma is drawn to Colin and his brother, Roddy. She introduces them to her troubled neighbor Alston Egerton, who has a clandestine relationship with Stephen Kitts, the soldier out for Colin’s blood.

As they all become entangled in a twisted web of love, jealousy, desire, and betrayal, the war rages on around them. Resentful at being forced into servitude and forbidden from being with the woman he loves, Colin puts his plan for vengeance into motion, though it will have disastrous consequences for all of them.

Secrets are revealed and relationships are torn apart. With the country teetering on the brink of ruin, Emma fights to survive, Alston is forced to confront his demons, and Colin must decide whether his burning desire to fight for justice is worth sacrificing a future with the woman he loves.

Historical Inspirations

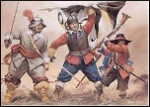

Royalists

The Royalists, or Cavaliers, fought on behalf of the king and his divine right to rule. They were known for wearing bold clothing and having elitist social and political views. Their long curls, feathered hats, tall leather boots, and fine tunics earned them the nickname of Cavalier by supporters of Parliament. In general, support for the Royalists was strong in northern and western England and Wales, although there were pockets of supporters all throughout England.

The Royalists, or Cavaliers, fought on behalf of the king and his divine right to rule. They were known for wearing bold clothing and having elitist social and political views. Their long curls, feathered hats, tall leather boots, and fine tunics earned them the nickname of Cavalier by supporters of Parliament. In general, support for the Royalists was strong in northern and western England and Wales, although there were pockets of supporters all throughout England.

Parliamentarians

Parliamentarians, or Roundheads, opposed the king’s desire to rule with absolute power, believing in a constitutional monarchy with Parliament having supreme rule over executive decisions. Although not all of the soldiers wore their hair closely cropped, many did and that started the use of the derogatory term, Roundhead. For the most part, Puritans and Presbyterians supported Parliament even though some were nobles and granted peerage by a monarch. The majority of Parliamentarian support came from the south (including London), the midlands, and parts of the east.

Parliamentarians, or Roundheads, opposed the king’s desire to rule with absolute power, believing in a constitutional monarchy with Parliament having supreme rule over executive decisions. Although not all of the soldiers wore their hair closely cropped, many did and that started the use of the derogatory term, Roundhead. For the most part, Puritans and Presbyterians supported Parliament even though some were nobles and granted peerage by a monarch. The majority of Parliamentarian support came from the south (including London), the midlands, and parts of the east.

Charles Stuart 1600-1649

King Charles I ruled England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1625-1649. Almost from the beginning of his reign, the people of England questioned his judgment. First, he married a French Catholic, upsetting those who believed he would return the country to Catholicism. He also dissolved Parliament three times between 1625 and 1629. Furthermore, he upset the Scots by attempting to force Anglicanism on them. Then he fought with Parliament regarding his desire to use taxes as he pleased, including to fund the fight against the Irish rebellion. In January of 1642, he accused five Members of Parliament of high treason, infuriating other MPs. As a result, war ensued and Charles was eventually beheaded on January 30, 1649, at Whitehall Palace. This started the Commonwealth of England, the only period of time in England’s history when there was no monarchy. Charles is buried in St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Palace, where Henry VIII and Jane Seymour are also buried.

King Charles I ruled England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1625-1649. Almost from the beginning of his reign, the people of England questioned his judgment. First, he married a French Catholic, upsetting those who believed he would return the country to Catholicism. He also dissolved Parliament three times between 1625 and 1629. Furthermore, he upset the Scots by attempting to force Anglicanism on them. Then he fought with Parliament regarding his desire to use taxes as he pleased, including to fund the fight against the Irish rebellion. In January of 1642, he accused five Members of Parliament of high treason, infuriating other MPs. As a result, war ensued and Charles was eventually beheaded on January 30, 1649, at Whitehall Palace. This started the Commonwealth of England, the only period of time in England’s history when there was no monarchy. Charles is buried in St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Palace, where Henry VIII and Jane Seymour are also buried.

Prince Rupert 1619-1682

Prince Rupert, King Charles’ nephew, was appointed as the Commander of the Royalist cavalry at the age of 23. He won many victories during his command until a defeat in 1645 that resulted in his exile to Holland. He was known for his flamboyant dress and arrogant ways. He often took Boye, his pet hunting poodle, into battle with him. Roundheads and Puritans believed Boye to have magical powers that could allow him to shape-shift, speak, or foretell the future. He was even believed to have been able to catch flying bullets between his teeth. Boye died on the battlefield in 1644, and his owner, Prince Rupert died almost 40 years later in London.

Prince Rupert, King Charles’ nephew, was appointed as the Commander of the Royalist cavalry at the age of 23. He won many victories during his command until a defeat in 1645 that resulted in his exile to Holland. He was known for his flamboyant dress and arrogant ways. He often took Boye, his pet hunting poodle, into battle with him. Roundheads and Puritans believed Boye to have magical powers that could allow him to shape-shift, speak, or foretell the future. He was even believed to have been able to catch flying bullets between his teeth. Boye died on the battlefield in 1644, and his owner, Prince Rupert died almost 40 years later in London.

Oliver Cromwell 1599-1658

Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland during the Commonwealth, was gentry born in 1599 and rose to become one of England’s most notable rulers. In his early 30’s, he went through a religious crisis and became convinced he was meant to carry out God’s purpose. He spent the rest of his life as a radical Puritan. Although Cromwell lacked a background in military expertise, he quickly caught on and led the cavalry for the Parliamentarian cause. In 1645, he convinced Parliament to establish the New Model Army, a highly trained, well-disciplined army of righteous men. He fought sternly for the king’s execution in 1649 and shorty thereafter, defeated the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar, essentially ending the English Civil War. He was known to suffer from bouts of madness, where he would spontaneously break into fits of insane laughter or tears. He died in 1658, and at the beginning of the Restoration two years later his body was exhumed and hanged.

Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland during the Commonwealth, was gentry born in 1599 and rose to become one of England’s most notable rulers. In his early 30’s, he went through a religious crisis and became convinced he was meant to carry out God’s purpose. He spent the rest of his life as a radical Puritan. Although Cromwell lacked a background in military expertise, he quickly caught on and led the cavalry for the Parliamentarian cause. In 1645, he convinced Parliament to establish the New Model Army, a highly trained, well-disciplined army of righteous men. He fought sternly for the king’s execution in 1649 and shorty thereafter, defeated the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar, essentially ending the English Civil War. He was known to suffer from bouts of madness, where he would spontaneously break into fits of insane laughter or tears. He died in 1658, and at the beginning of the Restoration two years later his body was exhumed and hanged.

Lord General Thomas Fairfax 1612-1671

Thomas Fairfax joined Parliamentarian forces in 1642 and was made Commander-in Chief in 1645. He was responsible, along with Oliver Cromwell, for forming and training the New Model Army, which never lost a single battle under his leadership. Fairfax only wanted to punish King Charles for his misdeeds and when he realized Cromwell and Parliament sought the king’s death, he opposed them. He even tried to postpone the execution but his efforts were ineffective. The following year he resigned his command, disagreeing with Cromwell’s desire to go to war with Scotland. Fairfax retired and lived out the rest of his years at Nun Appleton in Yorkshire.

Thomas Fairfax joined Parliamentarian forces in 1642 and was made Commander-in Chief in 1645. He was responsible, along with Oliver Cromwell, for forming and training the New Model Army, which never lost a single battle under his leadership. Fairfax only wanted to punish King Charles for his misdeeds and when he realized Cromwell and Parliament sought the king’s death, he opposed them. He even tried to postpone the execution but his efforts were ineffective. The following year he resigned his command, disagreeing with Cromwell’s desire to go to war with Scotland. Fairfax retired and lived out the rest of his years at Nun Appleton in Yorkshire.

Yorkshire, England

Yorkshire is located in the northeastern part of England about 70 miles (as the crow flies) from the border with Scotland. At the time of the Civil War, it was an area of divided loyalties. The majority of those who resided in Yorkshire sided with the king and the royalists while some areas held steadfast with the Parliamentarians. One example is Hull, where the king was denied entry into the city at the beginning of the war.

Yorkshire is located in the northeastern part of England about 70 miles (as the crow flies) from the border with Scotland. At the time of the Civil War, it was an area of divided loyalties. The majority of those who resided in Yorkshire sided with the king and the royalists while some areas held steadfast with the Parliamentarians. One example is Hull, where the king was denied entry into the city at the beginning of the war.

17th Century Lantern Clock

These clocks were typically made out of brass and operated by a set of weights and balances. Craftsmen from Flanders and France moved to England during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign and set up shop in London to make these clocks found in only the wealthiest of homes. But with the growth of the middle class, the need arose for domestic clocks and these lantern clocks became quite popular. Prior to this, most people told time by referring to sundials and tower clocks on churches.

These clocks were typically made out of brass and operated by a set of weights and balances. Craftsmen from Flanders and France moved to England during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign and set up shop in London to make these clocks found in only the wealthiest of homes. But with the growth of the middle class, the need arose for domestic clocks and these lantern clocks became quite popular. Prior to this, most people told time by referring to sundials and tower clocks on churches.

Appleton Hall

The fictional Appleton Hall is based on Nun Appleton, the home of Thomas Fairfax. It was a grand estate located on pastoral and lush, wooded land that included parts of the River Wharfe. Today it no longer exists as it did when the Fairfax family resided there, as the original home was torn down in the early 18th century.

The fictional Appleton Hall is based on Nun Appleton, the home of Thomas Fairfax. It was a grand estate located on pastoral and lush, wooded land that included parts of the River Wharfe. Today it no longer exists as it did when the Fairfax family resided there, as the original home was torn down in the early 18th century.

Newsbooks

All of the newsbooks mentioned in the novel–Mercurius Britannicus, Mercurius Aulicus, Mercurius Pragmaticus, and Mercurius Politicus–were published before, during, and after the English Civil War. They are only a few of dozens that were created for the sole purpose of spreading propaganda throughout England. Some favored the Parliamentarians (Britannicus) and others favored the Royalists (Aulicus and Pragmaticus). Politicus was published during the Restoration.

All of the newsbooks mentioned in the novel–Mercurius Britannicus, Mercurius Aulicus, Mercurius Pragmaticus, and Mercurius Politicus–were published before, during, and after the English Civil War. They are only a few of dozens that were created for the sole purpose of spreading propaganda throughout England. Some favored the Parliamentarians (Britannicus) and others favored the Royalists (Aulicus and Pragmaticus). Politicus was published during the Restoration.

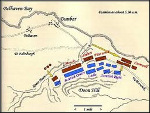

The Battle of Dunbar

This decisive battle fought in Scotland marked the end of the English Civil War. Cromwell’s forces defeated the Covenanters on September 3, 1650, after the Scottish army made the fateful decision to descend Doon Hill to fight the enemy. The Scots were chased for eight miles until Cromwell’s men captured them. The total number of Scots killed remains in question–Cromwell reported the number at 3,000 while Scottish reports said 800-900. The number of prisoners of war was also exaggerated by Cromwell as 10,000, but according to historical records on the number of men who started the march back to England, the count was likely closer to 5,000.

This decisive battle fought in Scotland marked the end of the English Civil War. Cromwell’s forces defeated the Covenanters on September 3, 1650, after the Scottish army made the fateful decision to descend Doon Hill to fight the enemy. The Scots were chased for eight miles until Cromwell’s men captured them. The total number of Scots killed remains in question–Cromwell reported the number at 3,000 while Scottish reports said 800-900. The number of prisoners of war was also exaggerated by Cromwell as 10,000, but according to historical records on the number of men who started the march back to England, the count was likely closer to 5,000.

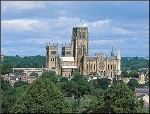

Durham Cathedral

Located in Durham, England, this cathedral acted as a temporary prison for the captured Scots from the battle of Dunbar. Out of the thousands of prisoners kept there, approximately 1,700 died during their imprisonment from disease and starvation due to inhumane conditions. They were rarely fed or given water and had to break apart pieces of the church’s furniture and adornments to use for firewood. Everything wooden was destroyed except for the large wall clock located in the south transept. All of the dead were buried in unmarked graves not far from the cathedral and the survivors were shipped to New England and sold into indentured servitude.

Located in Durham, England, this cathedral acted as a temporary prison for the captured Scots from the battle of Dunbar. Out of the thousands of prisoners kept there, approximately 1,700 died during their imprisonment from disease and starvation due to inhumane conditions. They were rarely fed or given water and had to break apart pieces of the church’s furniture and adornments to use for firewood. Everything wooden was destroyed except for the large wall clock located in the south transept. All of the dead were buried in unmarked graves not far from the cathedral and the survivors were shipped to New England and sold into indentured servitude.

Iron Works at Lynn

In November of 1650, about 150 prisoners were shipped from London to Boston aboard the Unity. When they arrived, Augustine Walker, the ship’s master, sold the men into indentured servitude for 20-30 pounds each. Sixty-one men were sold to John Giffard and sent to Iron Works in Lynn, Massachusetts. They were all given seven-year terms of indentured servitude, and while there, they stayed in a small two-room building called the ‘Scotchmen’s House.’ Seventeen of those men were eventually sent to work for William Awbrey in Boston at the factory and warehouse. All prisoners were released by 1656 or 1657.

In November of 1650, about 150 prisoners were shipped from London to Boston aboard the Unity. When they arrived, Augustine Walker, the ship’s master, sold the men into indentured servitude for 20-30 pounds each. Sixty-one men were sold to John Giffard and sent to Iron Works in Lynn, Massachusetts. They were all given seven-year terms of indentured servitude, and while there, they stayed in a small two-room building called the ‘Scotchmen’s House.’ Seventeen of those men were eventually sent to work for William Awbrey in Boston at the factory and warehouse. All prisoners were released by 1656 or 1657.

Order your copy today!