During the reign of King Charles I, the country is divided into two factions—the Royalists (or Cavaliers) who support the king and the Parliamentarians (or Roundheads) who oppose him. It’s a dangerous time in England, for brother has turned against brother and stating one’s allegiance to one side or the other could prove deadly. In Shame the Devil, the Blackburnes are destroyed by their loyalty to the king—lives are lost and futures are destroyed with a word.

Charles I

Queen Henrietta Maria

But how did this happen? How could a country turn on its king and demand he pay for his supposed transgressions with his life? What had he done that was so heinous to provoke Parliament to act against him? Actually there were several things, at least according to those who opposed him.

First, Charles believed in the divine right of kings. Basically, he only answered to God since he was chosen by God to sit on the throne. Second, he married a Catholic queen. This created concerns that the country would revert back to Catholicism after peacefully settling into Protestantism for almost a hundred years.

And lastly, Charles dissolved Parliament three times in his first four years which, naturally, didn’t keep him in Parliament’s good graces. When he raised his standard in August 1642 against them, it was the beginning of the bloodiest war ever fought on English soil.

In the end, Charles was captured, put on trial, and found guilty of treason. But how could a king be tried for treason? Who could put a king on trial? Wasn’t he above the law? None of it made sense.

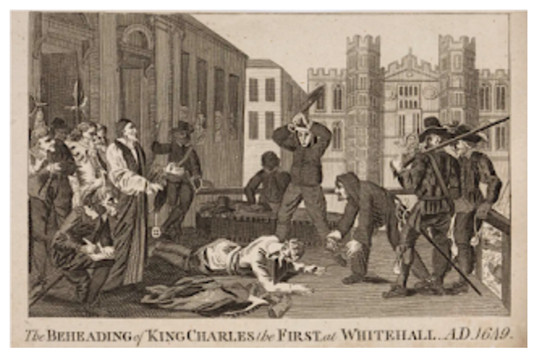

Nonetheless, hordes of people showed up on January 30th, 1649, to witness his execution. It was a cold, icy London morning. King Charles I awakened to a sharp knock on his bedchamber door at 10am for what would be the final hours of his life. He shrugged another shirt over the one he already wore so that his subjects would not think he was shivering from cowardice when he walked across St. James’s Park to Banqueting House in Whitehall. At 2 o’clock that afternoon, the king—dressed in black velvet, the white lace of his collar blowing in the frigid wind—climbed out the window of Banqueting House onto the sawdust-covered wooden planks of the scaffold that had been draped in black. The executioner’s block lay on the ground, a clear slight to the king, requiring him to lay prostrate for his own beheading. He handed over his outer clothing and the blue ribboned Order of the Garter he wore around his neck, then tucked his dark tresses into a white nightcap to make the executioner’s job easier.

The New Model Army was brought in to control the huge crowd gathered in Whitehall for the king’s execution. King Charles reiterated his innocence to a crowd that could not hear him through the wind and commotion. The heavily disguised executioner, who wore a fishnet over his wig and false beard, spoke kindly to the king. Charles lay prostrate, finished saying his prayers, and then stretched out his arms to signal he was ready. In one clean swipe, the executioner sliced off his head, then held it up for the crowd to see. A throng of onlookers edged its way to the scaffold to dip handkerchiefs in the royal blood that now stained the planks.

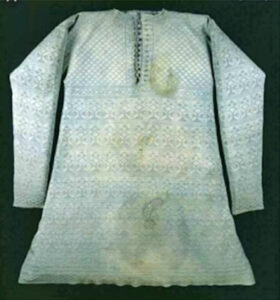

The waistcoat worn by King Charles I at his execution. The stains have been verified as bodily fluids , perhaps his blood.

The result? A dead king killed by his own people and a list of controversial reasons why it all had to happen. To this day, there remains disagreement as to whether King Charles I died as a martyr or a villain. What do you think?