One in five women were prostitutes at the time. Many of whom were wives earning an extra shilling or two to support their households.

“Moll Hackabout has arrived at the Bell Inn in Cheapside, fresh from the countryside, seeking employment as a seamstress or domestic servant. She stands, innocent and modestly attired, in front of Mother Needham, the brothel keeper, who is examining her youth & beauty.” William Hogarth, Plate 1 of 6, April 1733)

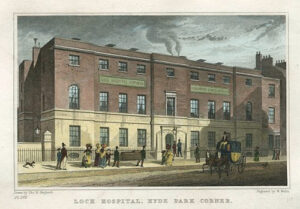

The London Lock Hospital was the first charitable hospital strictly designed to treat patients with venereal diseases. Founded in 1746 by William Bromfield, it was located in Grosvenor Place, near Hyde Park Corner. Upon opening, the staff included two surgeons, two physicians, one house surgeon, one matron, two nurses, six apothecaries, and a chaplain. There were other Lock hospitals prior to this one, but they specialized in treating leprosy. These hospitals disappeared when leprosy became less of a problem over the century, all but vanishing by the late 15th century. The London Lock emerged as a social necessity, considering one fifth of Londoners were estimated to have contracted syphilis by the age of thirty-five.

The meaning of the term “Lock” as it is used with these hospitals remains under debate. Some believe it refers to the patients being “locked” inside hospital quarters in isolation or quarantine. Others link it with the French term loque, meaning rag, to indicate the dressings that were used to cover the sores from leprosy or venereal disease. Another possibility is that the name refers to the restraints that were often used on patients at the leprosariums.

The London Lock Hospital in Grosvenor Place.

Unfortunately, many of the treatments offered were highly ineffective, and patients suffering from syphilis or syphilitic conditions rarely survived. If they were, by chance, released and later needed to return for treatment, they were out of luck. The London Lock had a policy to never readmit a patient once discharged. Being admitted wasn’t easy in the first place. A patient needed to get permission from the parish authorities (to ensure payment) and then obtain a letter of recommendation from the governor of the hospital. So much for privacy and discretion!

Once admitted, the patient—or as they were called, “Objects”—would receive a cot and be placed in a large open space with others. At their discretion, the surgeons would select a treatment, the standard being mercury for syphilis and urethral injections for gonorrhea.

Patients being treated for syphilis with mercury (inunctions and salivations).

Over the next two centuries, the London Lock Hospital went through many transformations. In 1792, the hospital opened the Lock Asylum wing to serve as a refuge for reformed prostitutes and fallen women who had been treated at the hospital and who had no home or life to return to. These women were given religious and moral instruction and taught skills, such as needlework, for working-class jobs. Eventually, it became a rescue home with additional units, including a maternity ward.