Death by hanging was used as a form of capital punishment in England as early as the fifth century. Other methods of execution found their way into history over the years as well, yet never managed to maintain the longevity of death by hanging. Castration, blinding, beheading, boiling, burning, and dismemberment all made an appearance in England between the time of William the Conqueror and the 18th century when hanging became the favoured method of punishment. Even children as young as seven were subject to pay for their crimes at the end of a rope.

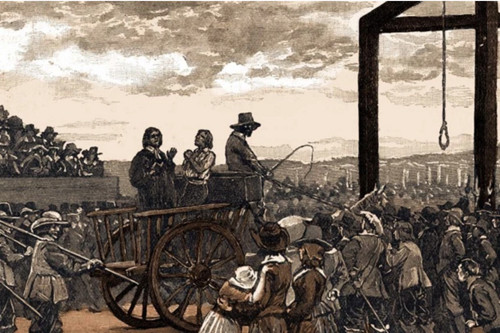

A 17th century hanging at Tyburn.

In the early 18th century, the British government mandated that anyone who survived his execution would either be hanged again, sent to the colonies, or set free. Although there are several recorded cases of convicted criminals surviving their hangings, the majority clearly did not. In a few cases, prisoners were accidentally decapitated during the process. But, as they say, accidents happen.

Those felons convicted of capital offenses—like murder—who didn’t survive their hangings, were additionally gibbeted or “hanged in chains” and placed on display after their deaths as carrion for birds and rodents. Like placing a traitor’s head and other body parts on the point of a pike and displaying them for all to see, gibbeting was used to warn citizens to behave within the confines of the law. The Murder Act of 1752 reinforced the practice of gibbeting. It was created “for better preventing the horrid crime of murder” and that “in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried” but instead be hanged in chains or publicly dissected. This punishment was mandated until 1834, when the Act was abolished.

The pirate Captain Kidd hanging in chains. (National Maritime Museum)

The mid to late 18th century was a particularly popular time for gibbeting. Between 1730 and the turn of the century, there were approximately 293 recorded cases of criminal corpses being gibbeted in England and Wales. London, of course, had the most instances of gibbeting, likely due to the large population and social and economic problems of the time.

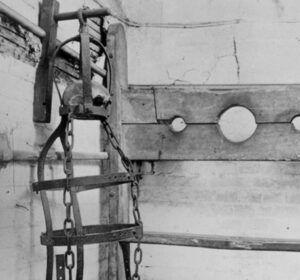

Possibly “Jack the Painter’s’ gibbet irons. Jack—or James Hill—was accused of burning down His Majesty’s Dockyard in Portsmouth in 1776. (Winchester Museum)

Gibbet irons that include John (the butcher) Bread’s skull fragment. He was convicted of murdering the town’s Deputy Mayor in 1742. (Rye Town Hall)

Gibbet irons that include John (the butcher) Bread’s skull fragment. He was convicted of murdering the town’s Deputy Mayor in 1742. (Rye Town Hall)

Female criminals were not gibbeted like male criminals. Because there was an increased interest in the female anatomy, women’s cadavers were often sold to anatomists and surgeons for research through dissection.

In 1868, approximately 30 years after gibbeting was no longer practiced, the last public hanging took place. Future executions were mainly performed within prison walls. It would be a long time before hanging would disappear completely from the British justice system, the last one happening in 1964.